THE (PROPOSED) STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK (SMF) of the Crossroads Community Neighborhood Partnership (CCNP) of the Urban Core Initiative

Introduction: The Strategic Integration of Neighborhood Capitals & Place-Based Initiatives

The Capital Crossroads Strategic Plan (September 2011) revolves around a set of community “strategic capitals” that the Urban Core Initiative renames as “neighborhood capitals.”

These “strategic” capitals form a framework that enables stakeholders of the Capital Crossroads Vision to assess the entire region’s current baseline and to set targeted performance levels for the entire region’s future development over the next several years. Applying these regional, “strategic” capitals to a specific locality, in this case the neighborhoods of the Urban Core of Des Moines, creates a unique and potentially replicable opportunity for the Capital Crossroads Vision to harness these broad planning concepts for use in specific, targeted neighborhoods, turning Strategic Capitals into Neighborhood Capitals.

Neighborhood-based community development efforts that aim to build upon and amplify neighborhood capital have been called “place-based initiatives” (See Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP). Ideas Into Action: “Place-Based Initiatives.” 2012). According to the CSSP, these kinds of geographically-defined place-based initiatives have emphasized the following:

- · Focus on particular neighborhood or a set of contiguous neighborhoods;

- · Work with neighborhood residents as leaders, “owners” and implementers of neighborhood transformation efforts;

- · Create strategic and accountable partnerships that engage multiple sectors and share accountability for results;

- · Collect, analyze, and use data for learning and accountability;

- · Design and implement strategies based on the best available evidence of what works;

- · Develop financing approaches that better align and target resources;

- · Address policy and regulatory issues;

- · Use sophisticated communications strategies to build public and political will; and

- · Deepen organizational and leadership capacity.

The PROPOSED Strategic Management Framework (SMF) of the Urban Core Initiative links a.) Capital Crossroads’ strategic capitals and b.) lessons learned from national and local place-based initiatives, particularly lessons learned from Making Connections. According to the CSSP, the next generation of federal, state, local, and philanthropic investments are well advised to acknowledge and respond to the following findings (See Center for the Study of Social Policy. Ideas Into Action: “Lesson Learned.” 2012):

- · The rigorous pursuit of clearly defined results at the neighborhood level;

- · Building community capacity is essential to achieving and sustaining better results for children and families;

- · Sustaining community change requires the commitment of local organizations to steward an ongoing focus on results and building the capacity to achieve and sustain them; and

- · One of the most powerful tools to help communities develop and sustain community change efforts is results-oriented, demand-driven technical assistance.

The Performance Blueprint within the PROPOSED SMF of the CCNP

Expanding upon the successful tools and practices of the United Way of Central Iowa (UWCI) (i.e., Results Scorecard and Efforts to Outcomes), the PROPOSED SMF makes use of a comprehensive and dynamic logic model called the “Performance Blueprint” (Longo 2004 a&b, 2002, See Figure 1).

Figure 1

Performance Blueprint:

How Resources will be Converted into Sustainable Outcomes

(Adaptation of Longo 2004 a & b, 2002)

The “Performance Blueprint,” embedded within the PROPOSED SMF, enables the CCNP to provide the kind of technical assistance and capacity-building support called for by the CSSP and other sources of lessons learned so as to address the needs of a broader range of neighborhood-focused, community-based, service-delivery providers, whether they are funded by the United Way or not. However, service providers constitute only one type of stakeholder whose needs and interests are addressed by the Performance Blueprint, other stakeholders include: neighborhood residents, neighborhood associations and boards, benefactors, investors, developers, financial institutions, planners, organizers, media outlets, and other entities representing the public, private, and not-for-profit sectors.

Since there is, in fact, such a complex constellation of stakeholders representing multiple sectors, institutions, and organizations, each with its own mission and corresponding set of monitoring and evaluation traditions and practices, there is a fundamental need – from the neighborhood’s perspective – for a COMMON VOCABULARY (language), a common logical framework, and a common visual representation to align and unite all providers, all stakeholders, and all targeted internal and external information consumers. In many ways the Performance Blueprint anticipates and accommodates this pluralism and diversity among stakeholders. For example, it equips the PROPOSED SMF with the flexibility to preserve individuality and autonomy among service providers, on one hand, while supporting systemic centrality and collaborative alignment on the other. There is no doubt that some neighborhoods in Des Moines have benefitted from community-development initiatives in the past even if these programs were only partially successful. Lessons learned and other studies suggest that the quantity, quality, and sustainability of these sorts of relatively isolated accomplishments can be significantly increased, and, as some research indicates, converged into a “collective impact (Kania, J. & Kramer, M. (2011).” Using the Performance Blueprint, the PROPOSED SMF aims to “map out,” for planning and evaluation purposes, the moving parts and tactical details of all strategies being performed in a given neighborhood so as to identify who the targeted populations and/or neighborhood conditions are, who the direct and indirect service providers are, what level of collaboration is expected, what collect impact is intended, and what sorts of resources are needed for effective execution.

Operation of the Performance Blueprint

As shown in Figure 1 (under “Expected Outputs), the Performance Blueprint incorporates the work of Mark Friedman, whose Results Scorecard and Efforts to Outcomes (ETO) models are already routinely used by United Way to document the efforts of funded and non-funded community-based organizations. The Performance Blueprint builds upon and expands the United Way’s performance measurement and management capacity by anticipating a broader spectrum of research and evaluation purposes; moreover, as the technical and organizational basis of both the performance management system and the MOU, it will validate and drive the required “learning” required to increase the likelihood of outcome attainment. Friedman’s effort-effect distinction is crucial to the function and utility of the Performance Blueprint in a cyclical and parallel manner; from RESOURCE management/allocation to OUTCOME approximation/attainment, questions related to “effort” (i.e., How much is being done?/How well is it being done?) and “effect” (i.e., Is anybody or any given condition any better off?) are both tied for first place.

The Performance Blueprint is both an evaluation and a planning tool, meaning that it can function both prospectively and retrospectively. It also operates on the collective level to facilitate the tracking of the combined efforts and effects of all direct and indirect service providers and on the individual level to facilitate the tracking of the specific efforts and effects of individual service providers. Moreover, the components of the Performance Blueprint can be organized into steps so that the logic model can also function to a significant extent as a theory of change mechanism. Figure 1 shows how stakeholders can use the Performance Blueprint – initially and routinely – to formalize mission and vision statements, establish broad community outcomes, set organizational priorities and values, define and target performance measures, make revisions when appropriate, raise research questions, identify emergent developments, and allocate resources accordingly.

Performance Blueprint as a Planning Tool

By following the following steps, the Performance Blueprint can be used to “map out” a strategy prospectively:

1. What are the targeted community’s desired Outcomes? How does it want to develop and advance its Neighborhood Capital? Where does it want to be in 5, 10, 20 years? How well does this dovetail with the Capital Crossroads Vision?

2. Which specific subpopulations, groups, conditions, etc. in the Core community should be identified as high-priority targets warranting immediate attention?

3. How and in what specific ways do the identified and targeted subpopulations, groups, conditions, etc. need to improve? How will these benefits and improvements be systematically and routinely monitored and documented? What existing community resources can be used? (The PROPOSED SMF meshes with the tools used by the United Way to drive cooperation and measure results.)

4. What specific strategies, programs, initiatives, activities, etc. need to be developed, adapted, or otherwise executed so that these targeted, high-priority populations and/or conditions can begin improve to benefit community development?

5. Who precisely is needed: planners, designers, executive officers, service-delivery personnel, volunteers, evaluators, etc., to develop, execute, implement, manage, and continuously improve the existing or needed strategies, programs, initiatives, activities, etc.?

6. What criteria, values, and principles will drive the execution of these strategies and the delivery of these services so that they can be appropriately customized for the community; integrated for the maximum benefit of the community; managed professionally, efficiently, and equitably; and consistent with the Capital Crossroads Vision?

7. How precisely will the quantity and quality of strategy execution, project implementation, and service delivery be systematically and routinely monitored and documented? What existing community resources can be used? As noted above, The Results Scorecard and the Efforts to Outcomes tools of United Way can be used to help answer these questions.

8. What resources are already available or still needed for these strategies to be executed efficiently, equitably, and effectively? How are “Neighborhood Capitals,” the community’s assets and liabilities, routinely identified and cultivated?

9. How will all stakeholders’ continually learn and improve? How will information and data needs be identified and met on a routine or ad hoc basis? How will information and data circulate throughout these systems to drive continuous improvement, ongoing performance measurement, and ad hoc program evaluation?

According to the Urban Institute and the Aspen Institute’s Roundtable on Community Change, place-based initiatives need to be structured into technical and organizational alignment in order to transform neighborhoods across multiple sectors (Smith 2011). These structures must be driven by community-focused principles of integrity, professionalism, credibility, stewardship, accountability, and transparency. Indeed, these are the core values of the Capital Crossroads Vision, the United Way of Central Iowa, and the Urban Core Initiative’s PROPOSED SMF. To dramatize these values the PROPOSED SMF combines routine performance measurement and ad hoc program evaluation GAO (2011) to map out collaborative strategies aimed at achieving a collective impact by facilitating the systematic collection and strategic use of program data and performance information on a routine and ad hoc basis in an intra- and inter-organizational, collaborative fashion for a variety of continuous improvement and evaluation purposes so as to support stakeholders in the approximation or attainment of the community’s desired outcomes.

One of the ways in which the PROPOSED SMF supports the achievement of a collective impact is by helping service providers remain faithful to and compliant with their individual funding streams and corresponding missions, on one hand, and by helping each of them become a collaborating “partner” in a structured and coordinated system of service delivery. Table 1 outlines how inter-organizational collaboration has been studied (Frey, et al. 2006 & Himmelman 2002) and how the notion of collaboration can be better understood and expressed in measurable terms for the benefit of all stakeholders.

Table 1

What Is and Isn’t Collaboration?

NETWORKING

|

COOPERATING

|

COORDINATING

|

COLLABORATING

|

Providers are vaguely aware of their similar community missions and inter-relationships

|

Providers are moderately aware of their similar community missions and potential inter-relationships

|

Providers are actively aware of their similar missions, strategic inter-relationships, and potential combined impact

|

Partners are pro-active, formal, and explicit about their shared mission, strategic inter-relationships, and combined impact

|

Providers occasionally communicate (email, meetings, etc.)

|

Providers occasionally communicate (email, meetings, etc.)

|

Providers regularly communicate (email, meetings, etc.)

|

Partners formally and routinely communicate (email, meetings, etc.)

|

Providers always make decisions independently

|

Providers generally make decisions independently

|

Providers occasionally make joint decisions

|

Partners formally and routinely make joint, inclusive decisions for the benefit of all stakeholders

|

Providers rarely exchange information for mutual benefit

|

Providers occasionally exchange data and information for mutual benefit

|

Providers regularly exchange data and information for mutual benefit

|

Partners formally and regularly exchange data and information for mutual benefit

|

| |

Providers may share resources

|

Partners formally and routinely share resources

|

| | |

Partners use the Performance Blueprint, engage routinely in the Performance Management System, and follow the Lifecycle

|

Adaptation of Frey, et al. (2006) and Himmelman (2002)

See Attachment A for Himmelman’s rendition of Collaboration.

The Performance Blueprint, by explicitly mapping the strategies of “partnering” service providers, sheds light on overlapping missions and shared opportunities. It sets forth criteria for stakeholders to use routinely to determine to what extent collaboration is, in fact, taking place for the benefit of approximating or achieving a collective impact. These criteria are included among those that constitute the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that participating service providers are expected to sign in order to become affiliated “partners” in the Urban Core Initiative’s CCNP. This will be addressed in more detail below.

The ultimate aim of the PROPOSED SMF is to ensure that dedicated resources are managed and allocated deliberately and in a transparent, data-driven fashion by all decision makers, that the proposed strategies and activities be executed collaboratively, efficiently, and equitably by all service-providing partners, that all internal and external stakeholders are represented and their voices are legitimized, and that these intentional, inclusive, and transparent efforts will produce a meaningful and sustainable impact for the benefit of the targeted residents as well as the conditions in which they live.

Continuous Improvement & Learning

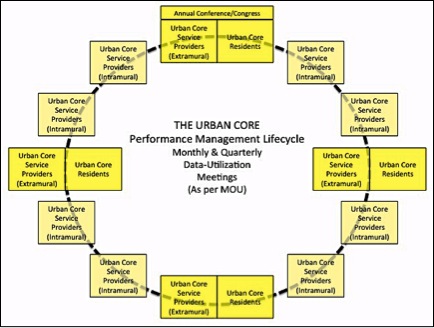

Consistent with Eckhart-Queenan and Forti ( 2011), the PROPOSED SMF incorporates a continuous improvement and learning plan designed to inform all stakeholders with legitimate information needs. Figure 2 is a depiction of the Performance Management Lifecycle that will address stakeholders’ needs.

Figure 2

Performance Management Lifecycle

The CCNP staff and collaborators will meet initially with a professional facilitator a.) to become familiar with the Performance Blueprint and the performance management system, b.) use the Performance Blueprint to finalize the initiative’s mission and vision statements, select, and target the performance measures that will be used to assess collective and individual performance, and c.) to finalize the evaluation criteria and performance expectations of the MOU that they will sign at that meeting.

Thereafter the CCNP staff and collaborators with the professional facilitator will meet on a monthly basis a.) to review program data and performance information in relation to previously targeted metrics, b.) review vision and mission statements, goals, targets, etc. for possible revision, and c.) confirm the direction or discuss the need for mid-course adjustments. The Performance Blueprint will be used as the explanatory framework to discuss the operational and strategic challenges related to implementation. In anticipation of these meetings the Evaluation and Learning Consultant will be available to help members of the performance management team prepare properly.

On a quarterly basis additional stakeholders, including neighborhood residents, will be invited to join the CCNP staff, collaborators, and professional facilitator at their monthly meetings. The Performance Blueprint will be used at these meeting as well as the explanatory framework a.) to discuss the operational and strategic challenges related to implementation, b.) share performance information, c.) offer progress reports, and d.) conduct listening sessions. In anticipation of these quarterly meetings the professional facilitator will be available to help staff and collaborators prepare presentations in advance for public consumption and to satisfy any external performance reporting.

In conclusion, for the Urban Core Initiative to take full advantage of the official community momentum and trajectory of the Capital Crossroads Plan and to honor all of the prominent public- and private-sector proponents and stakeholders who have endorsed it, it is incumbent upon the CCNP staff, collaborators, and residents to acknowledge the momentum of the United Way of Central Iowa and its tools and practices and at the same time to incorporate and promote the use of the language of capitals when articulating outcomes, measuring their approximation and/or attainment, and identifying existing or needed community assets to reach and sustain the outcomes that will benefit the community.

References Cited (with embedded and/or accompanying hyperlinks)

Frey, B.B., Lohmeier, J.H., Lee, S.W., & Tollefson, N. (2006). “Measuring collaboration among grant partners.” American Journal of Evaluation, 27, 3, 383-392.) http://signetwork.org/content_page_assets/content_page_68/MeasuringCollaborationAmongGrantPartnersArticle.pdf

Friedman, M. A., DeLapp, Lynn, & Watson, Sara. (2001). “The Results and Performance Accountability Implementation Guide.” Retrieved July 2012 from RAGUIDE Website http://www.raguide.org.

Attachment A

Collaboration (A. Himmelman 2002)